5 Questions with André Dao

André Dao is a writer and member of the

Manus Recording Project Collective.

No.1

Let’s start from the beginning: what spurred the formation of the Manus Recording Project Collective (MRPC)? And how did ‘Sitting by the Fence near the Jungle’ come about through that?

The Manus Recording Project Collective (MRPC) came out of an earlier project, The Messenger podcast, which started back in 2017. In The Messenger, Abdul Aziz Muhamat sent voice messages over WhatsApp on a smuggled phone from inside the Manus Island detention centre to Michael Green in Melbourne. The podcast essentially consisted of the voice messages Aziz and Michael sent each other, stitched together with some voiceover narration from Michael, to form a narrative about daily life in detention. At the same time, the narrative followed Australia’s border policies culminating in the official closure of the centre and the drawn out siege which followed as the detainees, including Aziz, took over the centre for 24 days.

Then in 2018 Joel Stern and James Parker approached us about using some of The Messenger archive as part of the ‘Eavesdropping’ exhibition they were curating at the Ian Potter Museum. But with Aziz and other refugees on Manus still imprisoned by the Australian Government, there seemed to be an imperative to create something new. Artistically, we were also interested in creating a work that resisted the drive towards narrative—with all the reductions and intermediaries that that implies—that characterises non-fiction podcasts.

So the MRPC—a riff on the official acronym for the centre—formed in response to that commission, beginning with Aziz and then with five other men whom Michael had met on a visit to Manus: Behrouz Boochani, Shamindan Kanapathi, Samad Abdul, Kazem Kazemi and Farhad Bandesh. Later, for a 2020 iteration of the project, Farhad Rahmati, Yasin Abdallah and Thanush Selvraj also joined the collective. Alongside Michael, Jon Tjhia and I were the other Melbourne-based members. At the centre of the two works the MRPC created together was a consistent form: a daily, ten-minute audio recording made by one of the men imprisoned on Manus—and later, in detention centres and hotel rooms in Port Moresby, Brisbane, and Melbourne.

As for ‘Sitting by the Fence near the Jungle’, it’s a collection of responses to the MRPC by academics and artists. The essays were originally published in the academic journal Law Text Culture and have now been republished in Disclaimer, the journal published by Liquid Architecture. Together, the responses highlight the extraordinary artistic and scholarly attention the MRPC has received—which is all the more extraordinary when you consider the interminability and intractability of the politics of detention. The careful, moving and intelligent responses to the MRPC’s work is a testament, I think, to how the ten-minute audio recordings resisted easy assimilation into existing frameworks for understanding the “refugee problem”.

No.2

In an interview you conducted with Behrouz Boochani, he said, “[…] art is the most powerful language to share this story, to tell this tragedy, not journalism.” I think the MRPC sits at the intersection of both mediums—bridging that divide, so to speak. How do you think you utilise the functions of both art and journalism to communicate these abhorrent human rights injustices to a wider public?

There was a timeliness to the recordings that had something like the public service function of journalism: in ‘how are you today’, the MRPC’s first work, the audience heard recordings play in the gallery that had been recorded a matter of days—or even hours—before. That timeliness was reflected in the titles of the recordings: Samad, yesterday morning, talking about his studies and listening to music; Shamindan, yesterday, in his room recovering from a migraine. And sometimes the recordings did function as a kind of reportage: the listener might hear about the latest suicide attempt, or hear an interview with a man on hunger strike.

But more often than not, the men chose to record the utterly un-newsworthy: cooking, exercising, listening to music, thinking, doing nothing at all. As I understand it, Behrouz’s critique of journalistic language is that because it is driven towards the sensational, the sound bite, because of the way it reaches for readymade images and phrases, it fails to capture the reality of life in detention. The wager the MRPC makes is that a very different kind of language—what Behrouz calls an artistic language—might do what NGO reports and journalism cannot.

No.3

When I was listening to the recordings, I was reminded of Nikita Dhawan’s very useful term ‘hegemonic listening’. I’m curious about your choice with regards to focusing on every day activities (such as Aziz watching the World Cup, or Farhad making tea and listening to music) instead of the trauma and suffering that is often reported on; what is described as ‘“cochlear” and “non-cochlear” dimensions: the dialogue between what is and isn’t heard.’ How did you and your collaborators arrive at this decision? What were you actively trying to resist?

Yes, I think ‘hegemonic listening’ gets to the heart of it—where the hegemonic is that which determines what can be heard. I had been thinking that we were trying to resist the commodification of suffering on the one hand, and compassion fatigue on the other, but now I see that commodification and fatigue are only two of the many kinds of injustices that result from ‘hegemonic listening’. So really what we wanted to resist were ways of listening that render people imprisoned in detention centres illegible and unintelligible. Another way of putting it is that far too many journalists, lawyers, advocates and campaigners are trained to hear from the mouth of the refugee only a cry of pain—or at best a claim of some kind, to better conditions, to be allowed in. Everything else—sexual desire, artistic ambitions, shame, boredom, joy, friendship, solidarity—can’t be heard through the usual channels.

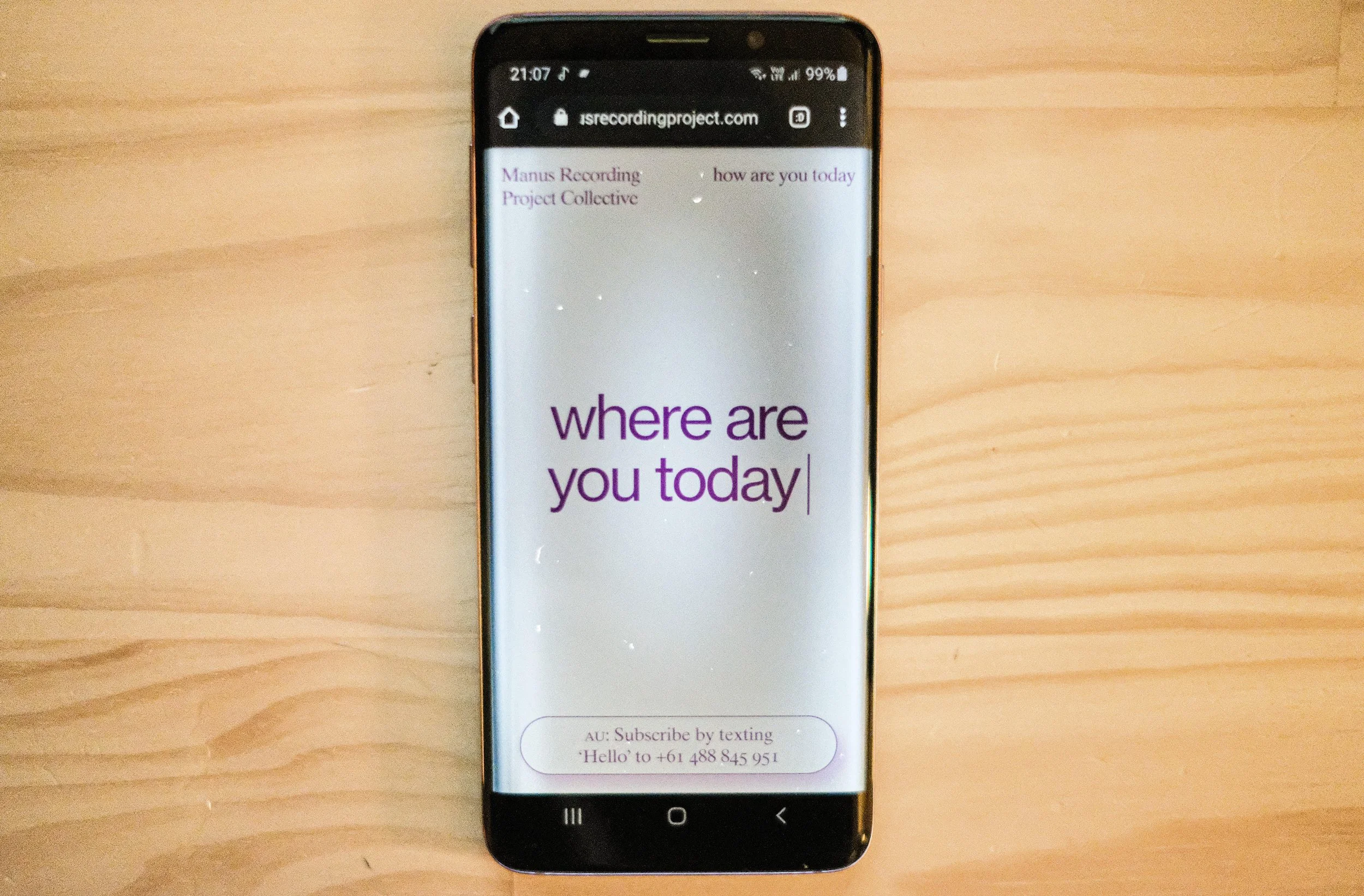

The decision to record the banal, the every day—the title ‘how are you today’ was a tribute to the banality, the inadequacy, but also the necessity of the greeting with which communications between Melbourne and Manus always began’—that goes some way, I think, to resisting the usual patterns of listening. For what can you make of a ten-minute recording of Kazem having a shower? It requires a different kind of listening. First of all, you have to listen for the context—the non-cochlear element, as James and Joel say in their essay—because that context, that Kazem is having a shower in a prison built and run by the Australian government, is what helps you make sense of what you’re hearing. So you have to learn to listen for that context, for what connects you to this scene—you’re listening for what Emma K. Russell calls the carceral atmospheres, the violent infrastructure that imprisons these men. You’re listening for your own complicity. It’s a point we pushed further in the second work, ‘where are you today’, by sending the recordings directly to subscribers’ phones, and making the details about the recording relational—using the geolocation on your phone, the site told you how far you are from where the recording was made (i.e. ‘You are 5km from Mantra Hotel, where Yasin made this recording’).

At the same time, though, you have to listen to the recording as it is—otherwise, if you only listen for the context, then you’re only engaging with the work conceptually. Which is another way of falling back into hegemonic listening. And the duration of each recording was deliberately chosen with this in mind: 10 minutes is too long for a soundbite, for easy digestion, but it is also doable. 10 minutes each day—that’s not a monumental work, the kind that almost no listener could ever get through. You’re supposed to actually listen to this work! So a non-hegemonic listening would hold the context in mind while also listening for the details of each recording—that is, essentially, what I try to do in my contribution to ‘Sitting by the Fence Near the Jungle’.

No.4

‘Sitting by the Fence near the Jungle’ is a collaboration, where you work together with asylum seekers you know to help tell their stories in a way that seeks to work against sentimentalism and sensationalism. How important was it for MRPC that the project was to be a collaboration? How did you maintain the integrity of the people you speak to and write about?

In one sense, our work was about the very possibility (or impossibility) of collaboration between artists in such absurdly unequal positions. Indeed, it’s about the (im)possibility of communication, of solidarity, across geographic, political, moral distance. ‘how are you today’, ‘where are you today’ —these are everyday questions that become very strange when you’re messaging across the militarised and punitive border.

So the MRPC was a constant exercise in finding ways to make collaboration and communication possible. One of those ways was the empty form, the ten-minute recording. Within that form, the recorder could make whatever choices he wanted about the content—if he wanted to draw attention to a hunger strike he’d interview the striker, if he wanted the audience to understand how he filled his days, he’d record a daily activity. If he woke up and felt only inertia and despair, then he could press record and wait ten minutes. Another way of making collaboration and communication possible was a continual process of checking-in: what do you think of this? Is this okay? Can we write this on social media? How does this sound? What should I record? Do you want me to send another?

At the same time, it was important not to trade in false equivalencies, to put our faith in a kind of formal equality. A more substantive equality between collective members meant recognising the power imbalances between us. That might involve Michael, Jon and I taking on the mundane tasks of sorting our technical difficulties, uploading the recordings to the distribution platform, liaising with the curators. It might also involve taking on less mundane decision-making responsibilities: the wording of didactics and dealing with legal concerns, fielding media requests and deciding who might best be able to speak on behalf of the collective.

No.5

What other projects do you have planned with the MRPC? Of course, we would prefer to live in a world where the collective has no reason to exist, but while Australia’s on- and offshore detention regime is ongoing, how do you think you can continue to amplify the voices of incarcerated asylum seekers and work towards an abolitionist future?

Almost all the members of the collective who had been imprisoned on Manus are now out in the community in one way or another. Some have found permanent protection in third countries: Aziz is in Switzerland after claiming asylum there when he arrived in Geneva to accept the Martin Ennals prize (which is the subject of the last two episodes of The Messenger); Behrouz was granted asylum in New Zealand; and Shamindan was resettled in Finland. Farhad R and Yasin were resettled in the US under the swap deal negotiated by Donald Trump and Malcolm Turnbull. Farhad B, Thanush and Kazem are in the community in Australia on temporary visas. Samad remains in Port Moresby.

All that means that the work of this specific collective, which had been formed around the specific geographic—and political, and temporal—site of Manus, is over. Individually, of course, we continue to work towards emancipatory futures in whatever ways we can. For me, personally, that comes back to the question of collaboration. In the interview included in ‘Sitting by the Fence near the Jungle’, Behrouz talks about the failure of this, and every other project over the last decade, to change Australia’s detention policies. The value of the MRPC, in his eyes, is historical. It’s a record of what happened. And I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how someone like me, a beneficiary of immense privileges, should approach this kind of work. How do I live with the risk of repeating unequal and violent power structures? One way might be to think of my task as the work of a caretaker or curator, someone assembling an archive of life and resistance in detention. Thinking of my role in the MRPC in this way helps me to understand how and why I might use my privileges and power—to take care of this fragile archive, so that what it records might travel to other sites and other times, and so contribute to the futures we do want.

Photo of the Mantra Hotel in Preston VIC, taken by Yasin Abdallah.

Arash Kamali Sarvestani and Behrouz Boochani, Chauka, Please Tell Us The Time (2017), video still, depicting the fence at Manus Regional Processing Centre, before its closure and detainees were moved to other facilities on the island.

Read and listen to Sitting by the Fence near the Jungle: Reflections on the Manus Recording Project Collective in Disclaimer here.

Each contribution to the dossier offers in-depth perspectives on the groundbreaking work of the collective in documenting Australia’s off-and-onshore detention regime from the inside through the production of an immense audio archive. Recordings from crucial works how are you today (2018) and where are you today (2020), originally commissioned by Liquid Architecture, are embedded throughout the dossier, so that reading and listening remain in direct dialogue. The total audio archive is accessible here.