5 Questions with Jamie Marina Lau

Jamie Marina Lau is a multidisciplinary artist and the author of Pink Mountain on Locust Island which was shortlisted for the 2019 Stella Prize and several other key literary awards.

With explorations focusing on language, Jamie's work meditates on a landscape exploring dis-location of culture and space.

No.1

Jamie, I remember when we first met you mentioned that you wrote Pink Mountain on Locust Island in three months. You were nineteen then, and of course, we all go through so much self-evolution/reinvention in our twenties especially. What did the momentum look like when you were writing Gunk Baby? Are you the kind of person who believes in writing every day, or does it come out in huge gushes each time?

My energy levels have definitely changed since nineteen haha. I wrote Gunk Baby while I was away on residency at a painter’s studio. It was within a week of getting back from Hong Kong in mid-2019. I had written scenes and characters before this time—actually while I was waiting for the first book to come out.

But the piecing together and the flow happened in a huge gush again, within the few weeks I had at that studio. The biggest difference between Pink Mountain and Gunk Baby is the process I took upon myself to reinvent it. I reinvented it twice on my own: when I was waiting for a few months to get edits back, and then while I was without a publisher last year. The staggered timing and the independence I had in returning to it allowed me to realise how much the writing process is able to reveal so much about yourself to you.

No.2

Do you recall your earliest aesthetic or artistic influences? At what point did you see them crystallising into something that made sense for your self and consequently your craft?

I’ve always felt most inspired by music actually. Any first instance of writing that I had when I was younger was probably prompted by the focus-state after experiencing something new-sounding, because it provided a new way of feeling. I was saying [to someone] the other day, when Eternity by Alice Coltrane was playing and we were writing: I tend to write freely when I feel that the room is buzzing with something impossible and strange, something that makes me so small compared to it.

Like, Eternity is such a cinematic experience and the incomprehensible tying together of a narrative so particular and rich—that’s definitely something that gives me the urge to explore form, particularly a form which can take you across lifetimes, across many eras of changing-your-mind and the inevitability of contradiction. I also grew up in a spiritual family, and I think it’s always caused me to try to understand everything I consumed from day-to-day life to what is being broadcasted, through parable and cyclicality.

No.3

One thing that intrigues me greatly is your naming conventions. Yuya, Trey, Monk, Leen, Jean-Paul, Santa Coy, Doms, etc—they are not ‘obvious’ or common names yet they work. How do you go about naming your characters?

I’ve probably picked them up or misremembered names from somewhere along the way to be honest haha. I guess to me it’s mostly about re-contextualising identity. As someone who grew up being asked to recite poetry to learn/better my English, the way something sits in your mouth phonetically is really interesting to me, the way nasality, roundness, inflection or intonation works. You begin to form an identity around the way people say your name: the way people mispronounce them, their gendered implications, the associations, etc. I like going with names that actively interact with the character, their identity and the way the world treats them. The name of the book usually comes first but the character names come as I write them.

No.4

Gunk Baby and Pink Mountain are very different books, but a similar sense of dread and ennui runs through both. Further, both Leen and Monk (the books’ two respective protagonists) are passive observers who react to the people around them as a way to understand themselves. Can you speak to this, and do you see the two books as being related or are they separate entities?

Reaction is actually such a central factor of writing stories to me—I think it allows us as storytellers to show and not tell, it prevents us from policing, lecturing, being close-minded and being un-empathetic to the multitude of experiences that exist in our periphery. It allows us to de-centre ourselves and explore how the world around us is built on systemic issues and conditioned prejudice, which trickle down to individuals—rather than it being about bad people or good people.

The classic narrator has immeasurable control over how the world around them is seen and felt (even if we are aware they are unreliable) and there is so much beauty in falling completely into another’s experience —if we were to treat every story equally. But in the past, each story hasn’t been, so there hasn’t been room to think about these things or analyse the biases or oppressive language that’s reinforced by a lot of the literature we are pointed to.

So I think literature (and film)—as forms, now more than ever—carry a great deal of responsibility, because it has contributed in shaping how we view the world and conduct ourselves within it. This is where the two books are similar. Both these books were projects in finding new ways for myself (who’s been incredibly affected by the way Asian women/people have been represented) to use such a connecting and illuminating form.

[So] this is where Leen and Monk, as passive (I prefer to use the words resigned/existentially bored lol) observers come in. The subtleties of their identity lie in how they are reacted to. By now they aren’t making any new discoveries, there is racism and they are living and benefiting within a system built on oppression. And they are both observers and targets of this. But there is never truly a ‘victim’ framework in either book—the characters are just only ever allowed to function how they are able to function in the sort of society they exist within, because of who they are and how they are seen on a mass level. It feels sadly inevitable. But playing with the concept that they as the resigned observers are the norm, and the world around them is what is alien—that’s what I’m interested in.

No.5

The psycho-geography you evoke—both in Gunk Baby and Pink Mountain—is very visceral. Characters tend to go about their business or encounter experiences in the one vicinity that they live in, and as a result the places become very familiar to the reader. To me, this is immediately reminiscent of two things: Wong Kar-wai films and the Sims computer games. Can you tell us a bit about your world-building process?

Wong Kar-wai films and Sims is really it. I’m not really sure how to explain my world-building process. I think I have photographic memory or just really image-based, associative memory. When I imagine a fictional place I’ll never be able to not remember it again, as if it were just as real as a place I’ve visited many times. I’m not sure if this is something everyone applies when writing fiction? But I find that really helpful.

I also spent a lot of time moving between places before I was a teenager, [and] in those formative years developing imagination and memory… I’m also early Gen Z and grew up on the internet. I guess those things combined really inspire me to create hybrid spaces or a space which feels nostalgic or familiar for many, based on how we consume and how the weather is—how we search for what feels like culture or tradition through these things. But I find that I really like to mesh many places I’ve been to together, seeking to find the common feeling between them.

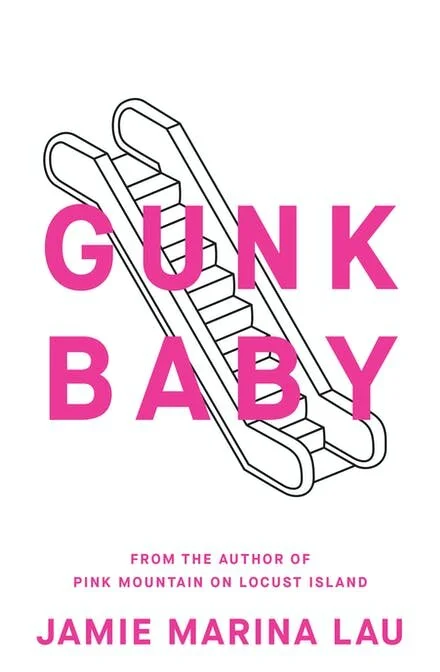

Gunk Baby is Jamie Marina Lau’s second novel. With a fierce intellect and masterful storytelling, Lau brings to life a world that is devastatingly close to our own. A world where consumerism drives us to buy things we don't need, where otherness can be used to manipulate, where a person's worth is measured by the role they play or the way they look and where protective services isn't about protecting others from violence but viciously punishing those who step outside the lines.

Now out with Hachette, or find it in all good bookstores.