5 Questions with Omar Musa

Omar Musa is a Malaysian-Australian rapper, poet and author from Queanbeyan. In his writing and music, he confronts the dark realities of Australian history and culture. He has released two solo hip hop records and an album with international duo MoneyKat.

Omar’s debut novel Here Come the Dogs has received widespread critical acclaim. His diverse career achievements include being long listed for the Miles Franklin Award and named one of the SMH’s Young Novelists of the Year in 2015, winning the Australian Poetry Slam in 2008, speaking at TEDx Sydney and appearing on ABC’s Q&A.

Killernova is his second poetry collection.

(Credit: Cole Bennetts)

No.1

You have a storied career in music and writing, and Killernova is your fourth book. Can you tell us how it came about?

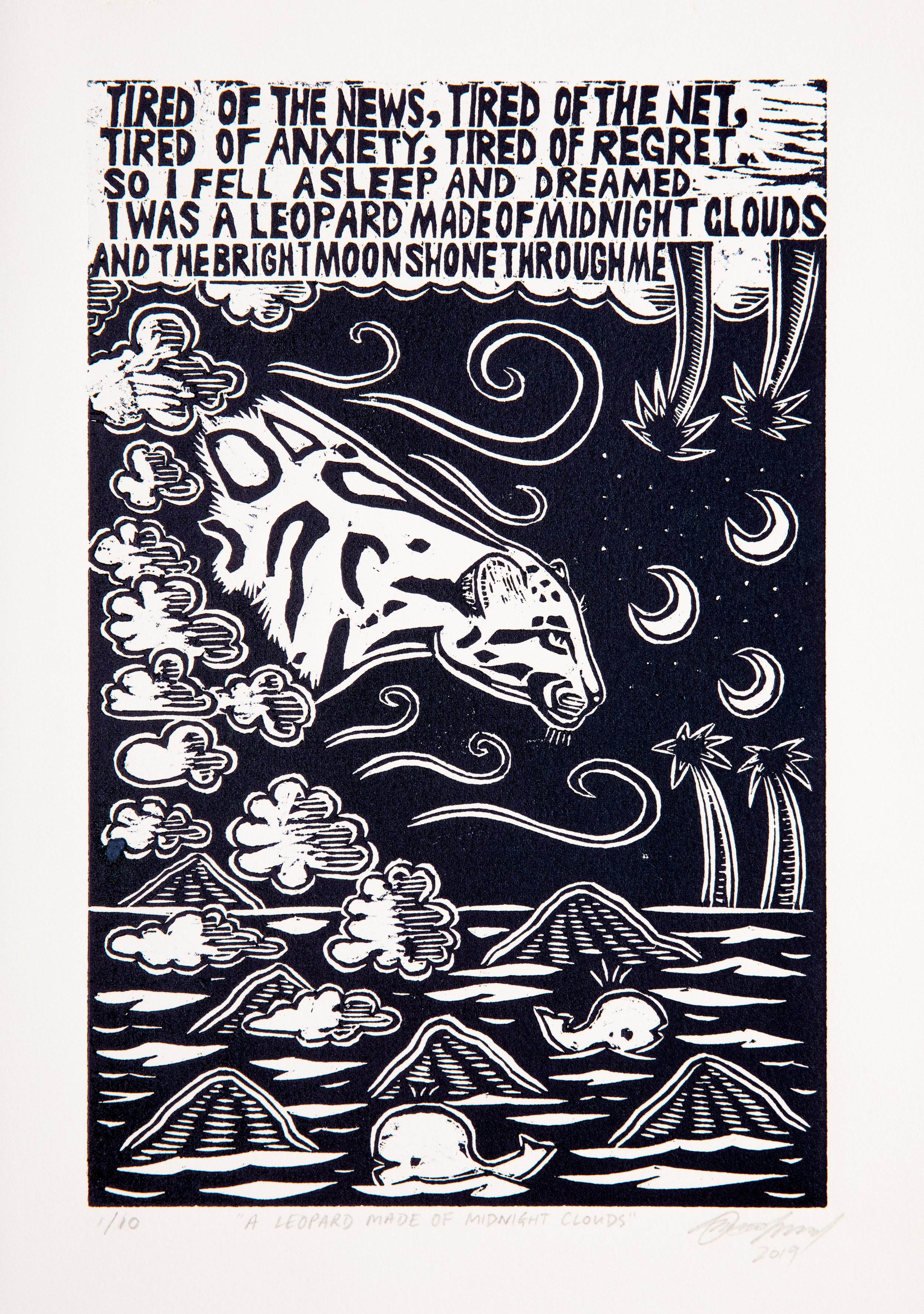

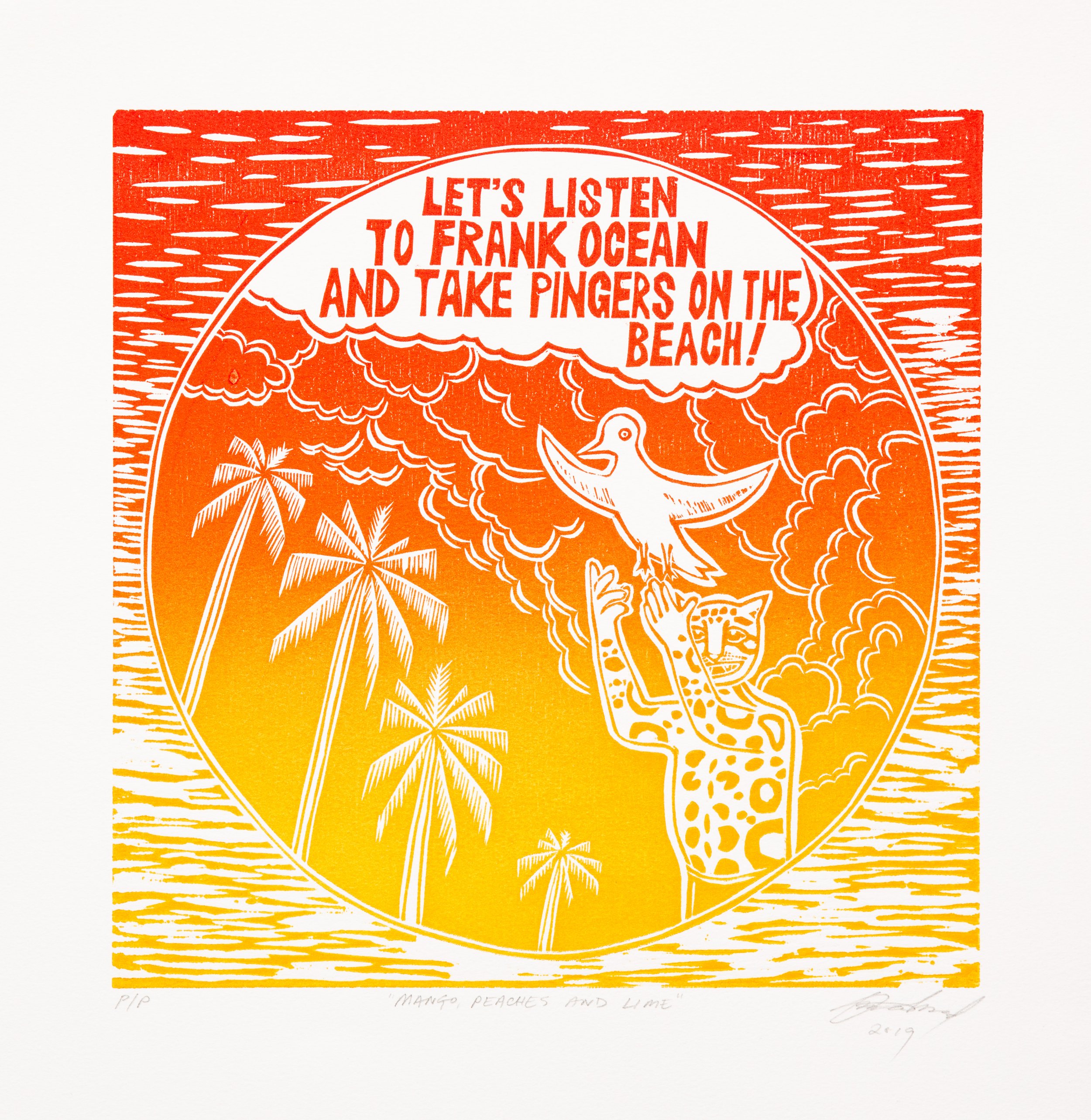

I guess I should start with how the woodcutting came about. I was in Borneo, travelling around and visiting family, when I was asked to perform at the Tamparuli Living Arts Centre, [which was], as far as I can tell, the only arts residency in Borneo. I saw that Aerick LostControl, an activist, punk rocker and woodcut artist from Sandakan (where my dad’s from), was running a woodcutting workshop. He is closely connected with the famous woodcut collective Pangrok Sulap. I’d been a huge fan of the Borneo woodcut style for ages, so I asked if I could join in, and sitting on the ground, he taught me to cut my designs into wood, roll the wood with ink, then press to paper or cloth by stamping with our feet. He gave me two pieces of wood and some tools to take with me, because he said that I had the type of concentration needed to be good at woodcutting. I became immediately addicted—I travelled to Sarawak with the wood and kept practicing. For some reason, it opened up a different part of my brain, and allowed me to be playful again, and have fun with creativity—something I’d lost over the years with my writing and performing. [Then] I got back to Australia, started linking up with printmakers and artists, picking their brains, and practicing, before heading back to Borneo and asking Aerick to be my guru for a few weeks. He taught me so much, and I took it from there. Within a couple of months, I’d had my first exhibition.

As to how the book came about? Well, my publisher, Nikki Christer from Penguin Australia, had mentioned to me a few years ago that she’d like to publish a book of my woodcuts, but I’d only been doing it a few months so I felt like an imposter. Earlier in the year, when thinking that I’d like to collect my works in one place in order celebrate this cool, unexpected turn in my artmaking and celebrate the people who helped me along the way, I remembered the conversation, and luckily, so did Nikki!

No.2

What really struck me while reading Killernova were the wood-cut accompaniments, which add another dimension to the collection, and which you write in the book’s introduction was a skill learned from Sabahan collective Pangrok Sulap, who had been inspired by the Yogyakartan collective Taring Padi. To my knowledge, there is a huge tradition of protest in these precedents, especially as they are tied in with punk/DIY and activist groups there. What do you think is the relationship between poetry, art and protest for you?

That’s a tricky one, you know. I’d say that most of my more well-known poems, like ‘My Generation’, ‘UnAustralia’ or ‘The Ranthem’ would fit into the category of protest poetry, and are influenced by the famous line by Bertolt Brecht ‘there was little we could do, but without us the leaders would have felt more secure.’

But even in those ones, I make sure to hold myself accountable a little bit, so that they are nuanced and I don’t come across as didactic, preachy or claiming to have all the answers. I’m glad those type of poems resonate in a way that shakes the beehive a bit, but I actually think most of my work fits into the category of confessional poetry, and is only perceived as protest poetry because it happens to be me, Omar Bin Musa, a brown, Muslim-Asian-Australian, who is making it, so in that context, merely speaking or putting pen to page seems like an act of resistance to some of the more toxic mythologies of Australia.

In Killernova, I’m obviously heavily influenced by the aesthetic of Taring Padi and Pangrok Sulap, and the book is clearly critical of corruption and logging in Borneo, but I replace slogans with poetic couplets, lines of narrative/personal stories or scraps of conversation. So, I’m not sure these poems neatly fit into the category of protest poetry/art. I aim for subtlety and range in my work, so bouncing between work that is political, personal, observational, and a weird mixture of all of them hopefully makes for complex art that operates on a number of levels.

No.3

You are also a slam poet and rapper. When you write a poem do you think about it in the context of it being performed, or do you write poetry first for the page then bring it to life after the fact?

I usually don’t think about whether it’s going to be a spoken piece or not. I just write my thoughts and feelings down in a whirlwind, although it usually becomes clear pretty quickly if it will work on stage or not, because in editing (even with prose) I’ll read the work aloud to make it flow better, or ferret out awkward phrasing, which makes itself known to you immediately when spoken. It’s very rare these days that I’ll actively think ‘this is going to be a performance piece’, but if I do, I’ll probably focus a bit more on adding internal rhyme and rhetorical devices in there.

No.4

There is a sense of both hope and melancholy in Killernova, as you celebrate semangat (spirit) yet mourn the loss of what could have been. How do you strike a balance between the two in your work?

It’s probably just reflective of my general state of being or personality: both seem to oscillate wildly between melancholy and darkness, as well as hope and exuberance. Having said that, there are times when I have to consciously sprinkle a little bit of hope into my poems, which have in the past leaned towards nihilism, almost as a self-affirming rallying cry to keep pushing forward, even though the world seems overwhelmingly bleak.

No.5

Who or what inspired you while in the process of writing Killernova?

Gardening and the natural world around me inspired me a lot during the writing of this book, which also coincided with lockdown. I did a lot of my thinking while walking along the Queanbeyan River, Googong Dam and Molonglo Gorge. Longing for and memories of Tamparuli, Semporna, Bario and the Mahakam River in Borneo inspired me a lot.

In terms of people, visual artists like Pangrok Sulap, Taring Padi, Jason Phu, Abdul Abdullah and Yee I-Lann are obvious influences. In terms of poets and writers, I reread a lot of Elizabeth Bishop and found that generative. I once heard that she aspired to three things while writing: ‘accuracy, spontaneity, mystery’. What an incredible triangulation. I had those three things written on a scrap of paper above my desk while I was making this book. Other literary touchstones for this were Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, the late Salleh Ben Joned, Simon Armitage, Brenda Shaughnessy, the Syrian poet Adunis, and Pascale Petit’s book Mama Amazonica.

In KILLERNOVA, grappling with his heritage, Omar Musa remixes this ancient art form with fiery poetry forged in the stars.

With equal parts swagger, humour and vulnerability, Musa charts a journey through the colonial history of South-East Asia, environmental destruction, oceans, bushfires, race in Australia, the isolation and addiction of COVID lockdown, family, lost love and, ultimately, recovery.

Relentlessly on beat, visually captivating and deceptively intimate, this is a collection of words and art that burns blindingly bright.

Now out with Penguin, or find it in all good bookstores.