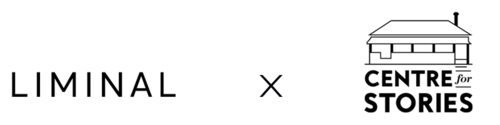

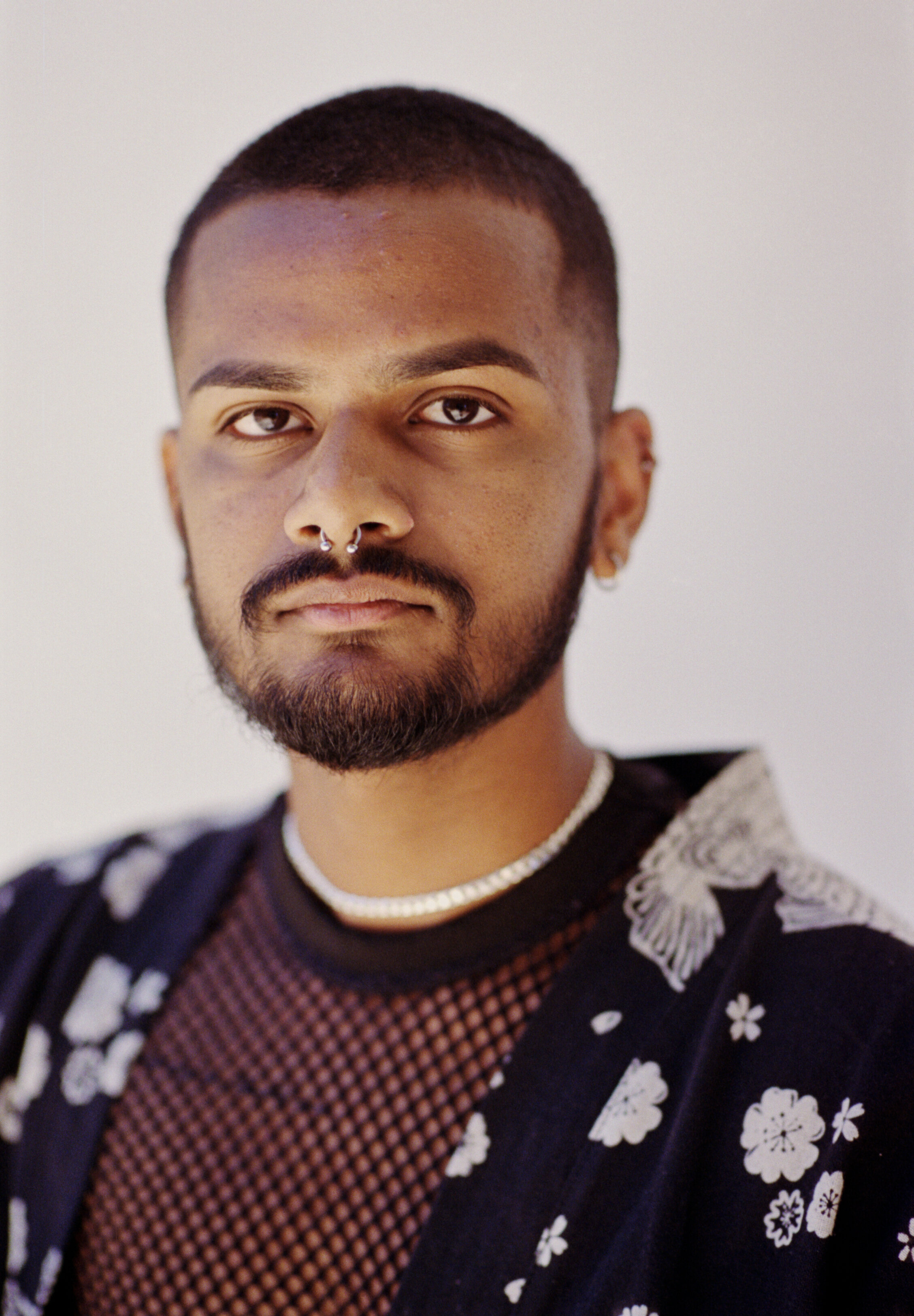

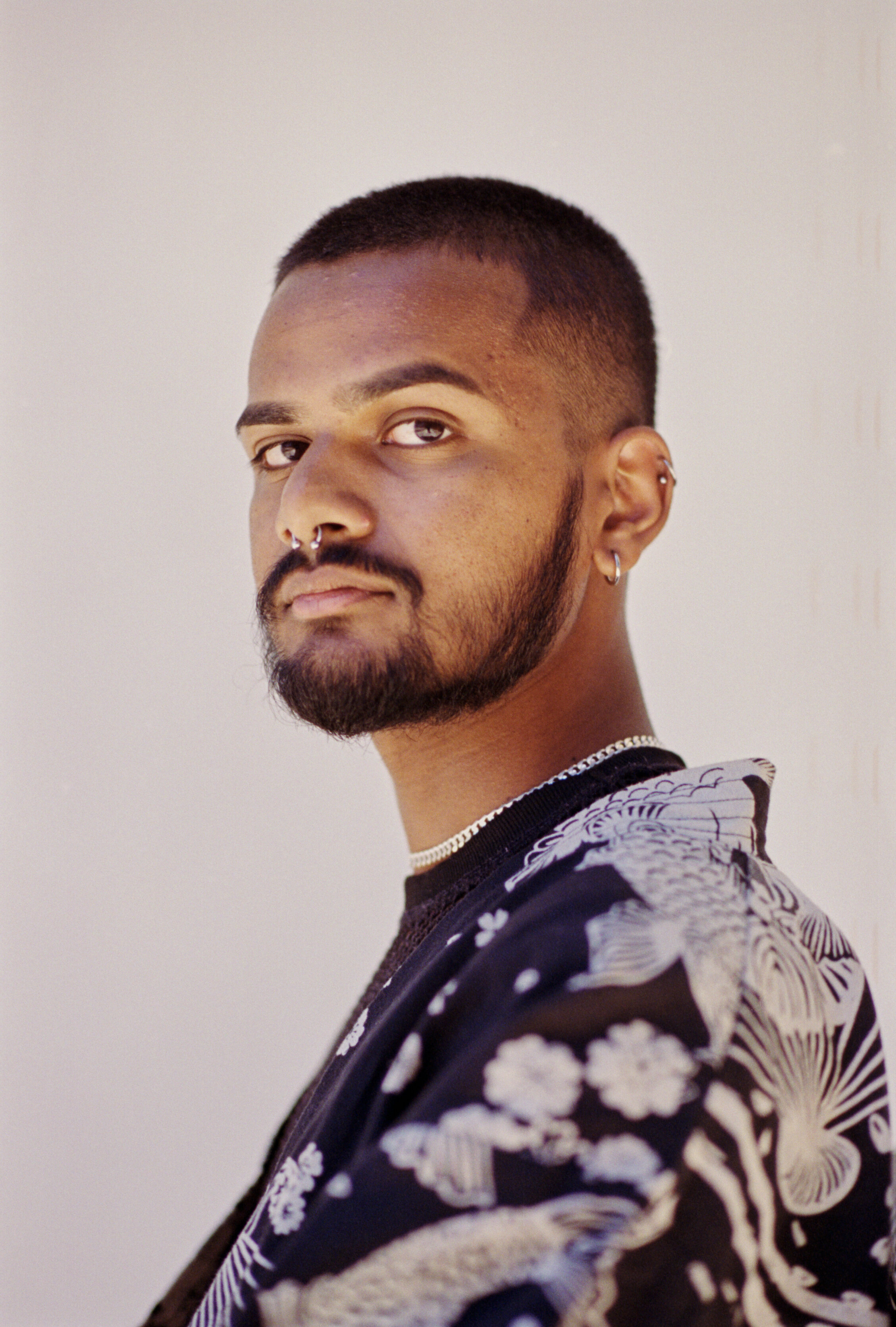

Interview #163 — Rushil D'cruz

by Robert Wood

Rushil D'cruz is a medical student at the University of Western Australia. He is also a musician and writer, whose work centres around concepts of religion, violence and systems of domination. Rushil grew up in Malaysia and Kalgoorlie in regional Western Australia.

Rushil spoke to Robert Wood about balance, home, and multitasking.

You spent your youth in both Malaysia and the mining town of Kalgoorlie, many hundreds of kilometres from Perth. What do you think are the similarities and the differences between both places?

It is extremely hard to think of any commonalities between the two. I moved from lush, densely populated cities to the scarce, empty plains of Kalgoorlie. Where once I lived around mountains and fog, here was flatness and red dirt. I remember vividly waking up one morning on a family vacation to Langkawi and over breakfast, looking out the window and seeing a gorgeous hornbill looking back at me, perched in the branches of a tree. Malaysia is a place where you are awoken daily to the sounds of wildlife and people and the smell of food. The people are not the same, the school systems are so vastly different (coming to Australia was my first experience in a co-ed school) and, most tragically, the food is not the same.

There is this loudness and brashness of the Malaysian style of speaking that is so different from the polite nature of Australians, even those rowdy bloke-y blokes out in the mines. There is community in those neighbourhoods of my childhood, where we would celebrate Christmas, New Years, Chinese New Years, Deepavali and Ramadan: all together, regardless of the religion you subscribed to or your ethnicity.

It is often unfruitful to think in dichotomies, yet, the cities of Malaysia and Kalgoorlie might truly exist as such.

We are both Malayalis, and, my mother’s last name is the same as your last name; so perhaps, we are related in some way. I know you have not travelled to India, but am curious to know how you imagine it. What does India mean to you?

I hope we’re related, that would in some way make me an uncle to your baby!

My relationship with India is only now starting to grow. This I attribute to many years of conditioning during my adolescence. My parents were unable to teach me much about my culture as they were often working a lot to provide for my siblings and I, and, we had no other family or friends here. I would often cringe against people and rituals of my culture, and was quick to distance myself from the label ‘FOB’ or any remnant of an accent.

It has been in this year, by reading and exposing myself to Indian media that I have developed a deep appreciation for our culture and history: how far back it stretches and how it situates me in this time and place. Taking the time to unpack all this hatred conditioned into me has proved to be such a spiritually and emotionally fulfilling exercise.

India to me now feels appropriately ‘the motherland’, the roots from which all the branches of the diaspora stem from. And just like a root system, I appreciate its deep complexity and continuing growth. Where once the words ‘Malayali’ or ‘Gujurati’ meant little to me, now I see this informs social status, forms of work, and geopolitical connections. There is much I still have to learn about India’s history, let alone its current political and cultural climate.

I am still a little hesitant to visit India as I don’t speak Hindi or Malayalam but I hope to overcome this fear as I grow and learn more.

This informs your writing in some way, and, I am thinking of a short story you wrote called ‘Vulture’, which has elements of the surreal but also touching engagements with alienation and family. How do you go about crafting stories?

More than narratives or the events that I write about, I recall dialogue quite vividly and so this is always my starting point. The buoyancy of dialogue, the way it can meander away from a subject yet still keep forward momentum is deeply fascinating to me. ‘Vulture’ starts off with a conversation about kurtas, a conversation which actually took place: it is both a conversation about kurtas and yet not about kurtas at all, about who belongs where and how we identify each other.

Dialogue is often sparring: listening, absorbing, deflecting, anticipating. Thus, it is intrinsically tied to my emotions in the moment. I think deeply about how the story made me feel and what that means about me, the way I was raised to view the world. I centre the story around myself and my feelings because I don’t want to speak for anyone else or assume anyone’s position on a set of events. This was my approach to ‘Good Men Doing Nothing’, and it allows me to navigate tender and traumatic topics in a way that I feel is responsible.

Recently I have been focused on simply telling events as they happen, minimising the fictional aspects of my writing. Again, this is tied to a desire to represent reality responsibly and in its fullness, providing a framework within which readers may better conceptualise their own emotions without placing the focus outside of the individual. Where there are hints of the supernatural, this stems from spiritual beliefs that I truly hold.

Writing is only one part of a varied practices, and, you have written for arts journals, make your own visual art, and you are a musician too. This is to say nothing of studying medicine. Talk to us about keeping all of these balls in the air.

With great difficulty.

Studying medicine has been the greatest challenge I have faced, not because it is difficult in itself (although it can be challenging), but because of the sacrifices I have had to make along the way. It has forced me to grow up quickly, to look deep within and prioritise what I need and my values. As such, much of my experience and work with art has had to fall to the wayside despite my love for the visual arts. What I have kept (music, writing and my studies) I have kept because I have no other choice. I would go mad without these outlets.

Much of the balancing act is learning to be patient with myself. Where I could work on music quite regularly in the past as well as write daily, now I have to space these out over the week. My approach has become more deliberate and thoughtful because of this, and I have had to incorporate self-love into everything I do. Where before I would craft stories and music to appeal to an audience (which may be a viable approach to making art for some), now I only have time to do things that I truly believe in or feel the pain of a burn-out. Everything must be done sustainably and in balance, and finding this balance is often 50% of the work.

Dialogue is often sparring: listening, absorbing, deflecting, anticipating.

Do all of these diverse interests have a common root? Is there something back there that influences all of them, that ties it together, if not neatly then at least helps explain your drive and passion?

Any work I have done in music, visual art and writing (‘the arts’) I have done because I sensed a vacuum in the current dialogue within these fields. These may be thematic or aesthetic. What drives my music in particular is the ideas (political) that I want to express that I do not currently have the skillset for. So I work to get my skills up to par and hopefully one day, I can bring these to fruition.

On the other hand, my medical studies are driven by my need to understand, to break things down to their simplest form and know the way the world works. So my studies and my art work hand-in-hand: one to understand this world and the other to be at peace with not understanding.

This is also a little optimistic. Truthfully, my drive comes from being raised to be working constantly and conditioned to want to be the best at what I do. Marooned on this island at such a young age, it often seemed the only times I was seen or heard by the community around me was when I was accomplishing something. This was how I grew up thinking respect was earned.

This was a fine way of thinking within the academic system where everything is graded and there are set points of achievements, but venturing into the arts made me very uncertain of what I had achieved and what was left for me to achieve. Do I place the bar at earning 200 streams on a song? 1000 streams? It’s all arbitrary and self-decided. It destroys the soul and spirit.

Now I find passion and fulfilment in opening up spaces for inclusivity and conversation. Where I have a voice and a skillset, I can push open doors in industry and allow others in. Creating community, through my specific love for words and people: this is my drive.

I have been thinking about your music for a little while—can you explain where things are at with your creative process and what you are working on right now?

Lots of different projects and songs are in various stages of development but mostly I’m still in the writing phase across all of them. I generally try to work on quite a few songs at once as it takes the pressure of a single being ‘perfect’. Some days I’ll hear a beat and a verse will immediately come to me that I know will work perfectly together, other times I’ll hear a clever turn of phrase in silence and work that into an existing verse or build a verse around that. Lots of cutting and pasting, lots of editing and trimming. I’m hoping by December to be into the recording and mixing phases so that I can have new content out either by the end of the year or top of 2021.

In terms of creative process, as I said before, I am learning to be patient with myself. In the past, I’ve found myself beating myself up because my skills haven’t been up to par with the message I’d like to deliver. Now, I’m working out the anxiety of having to constantly deliver content and spending quality time with my own work to make sure I’m happy with all aspects of it. My work now is sometimes poppy, sometimes melancholic, sometimes political, sometimes cocky: I’m learning to roll with my moods and keep rhyming regardless. There’s always some aspect of the craft to hone and ideas to experiment with.

Active listening is also playing a big role in how I study hip-hop now. It is hard to balance the overwhelming amount of new music with spending time in the intricate worlds some artists build, but it is the same in any field.

On the club event side of things, I’ve made the decision to go completely not-for-profit and only endorse and employ BIPOC individuals. I put together my own line-ups for my shows, handling the admin and financial side of my duo act and this decision has come from a place of understanding how much space I can take for myself without taking space away from those who may need it more. This is something I think every non-Indigenous person in so called Australia should grapple with: how much can you ethically make off stolen land?

Where can readers find your musical work?

I go by the name SUSHI and have songs on Spotify and Apple Music, some are on Soundcloud. If you live in Perth, my recommendation is to come to a live show because that’s where we perform unreleased music.

Finally, what does the summer hold for you?

A time to slow down after a busy and hard year and reflect. Read in the sun. Connect with those I love and strengthen our bonds.

Also: I’m 22. Drinking, going to raves, and nursing hangovers is definitely on the cards.

Do you have an advice for emerging musicians?

All that we need is right here. Look beyond our coasts for inspiration but do not idolise them or seek their validation. Australian youth need to believe there is something strong, worthwhile and valuable in our own voices without having approval from the USA and the UK. As Ruby Hamad writes in White Tears/Brown Scars, “… Australia, as ever, rarely acknowledges the value of anything unless it has an international stamp of approval.”

On a level even beyond that of music, this is what will strengthen our cultural identity, allow us to have the tough conversations that we as a nation have been avoiding for so long and forge a path for the future of this country.

Also, know what you’re doing it for. Live sustainably and ethically in all aspects of life, then living becomes its own reward.

Who are you inspired by?

Jay-Z. Griselda. Playboi Carti. Earl Sweatshirt. Yugen Blakrok. Malcolm X. Michael Gira of SWANS. My grandfather. Ali Smith. Russell Brand. bell hooks. My siblings. Albert Camus. My lovers: those in my past and those I have yet to meet.

What are you listening to?

Some Rap Songs - Earl Sweatshirt

Beat Konductor in India - Madlib

Descendants of Cain - KA

Future Nostalgia - Dua Lipa

Anything Griselda is putting out

What are you reading?

I’ve just finished Talking To My Country by Stan Grant and White Tears/Brown Scars by Ruby Hamad. Currently I’m reading Terra Nullius by Claire G. Coleman and Uzumaki by Junji Ito.

How do you practice self-care?

Burning candles and incense in my house. I find scents very calming. I meditate and journal daily. Reading. Being alone and having time to learn are very important to me.

Talking and taking walks with my mentors. Talking and taking walks with my mentors who have babies as an excuse to hang out with their babies.

What does being Asian-Australian mean to you?

It means to be a benefactor of white supremacy and colonialism, while also subject to its oppressive discriminations and prejudices. This puts us in a position to use the platforms and privileges that we have to elevate Indigenous voices.

It also means having to unpack traumas and ways we were conditioned to hate ourselves, our cultures and the Traditional Custodians of this land.

It means work. Work in the proudest, most fulfilling, most spiritual sense of the word.

Interview by Robert Wood

Photographs by Chris Gurney