Screens — Loev, Wadjda, Yellow Is Forbidden

By Adolfo Aranjuez

Loev

Sudhanshu Saria, 2015 // 92 mins // Netflix

While LGBTQIA+ films are plentiful on the various streaming platforms at our disposal, when it comes to queer content from Asia, it’s pretty slim pickings. Thankfully for us, there is Loev—and its having originated from India cannot be more apposite for a month commemorating the queer community’s milestones, given it was only in September 2018 that the country annulled its laws criminalising homosexual activity.

Alex and Sahil’s relationship is characterised by both devotion and growing exhaustion. It also appears to be open, with the sprightly Alex egging on his melancholic counterpart to relish his time with Jai, a sometime lover who’s in town for the weekend. While the New Yorker is in Mumbai for a business deal, there’s no denying that Sahil is really what’s on his mind. And, as with every narrative in which a couple’s predictable stability is rocked by a third person, Jai’s arrival creates a proverbial wedge: his consolatory ear and wholesale hotness, not to mention the fancy dinners, the elegant hotels, the flashy car, tease Sahil with an alternate life.

Notwithstanding the apparently dramatic stakes, the film is permeated by a subdued quality that challenges the otherwise-showy beats of mainstream queer cinema. A trip to the sublime Western Ghats may sound super intimate, but we rarely witness Jai and Sahil kissing, in any state of undress or even touching (and the pair are almost always in claustrophobic proximity). Instead, our focus is directed to acts of tenderness—sexual intention seemingly forestalled by chaste affection. By its final third, however, the film takes a dark turn (no spoilers, but also: content warning) and their bond is damaged irreparably.

As Loev was released prior to India’s change in legislation, these quiet and well-rendered scenes are thus also notable for their subversiveness. In this context, it’s beyond understandable for men (on screen and beyond it) to be both circumspect about their orientation—restraint as a means to avoid both risk to heart and risk to life—and rebellious in their expression of it in stolen moments. Enriching this insight into queerness are the film’s subtle commentaries on class, colonisation, the expatriate experience and the importance, in many Asian cultures, of saving face, of forgoing the ‘right’ thing for respectability.

I’ve written before about the extra significance of time for queer people, and this film is likewise bounded by it: Jai comes, then departs, after which Sahil and Alex must mend what’s left of their relationship. Contending with a society that polices agency and ownership of bodies, Sahil finds that time away, time apart, time having passed all give him a newfound grasp on what he desires, and deserves.

• • •

Wadjda

Haifaa Al Mansour, 2012 // 132 mins // SBS on Demand

Speaking of cinematic achievements, let’s not skimp on applause for the first ever film shot entirely in Saudi Arabia, which is also the first ever feature to have been directed by a Saudi woman. This nation is notoriously insular and conservative, characteristics that manifest acutely when it comes to women’s rights (or a prevailing lack thereof—Saudi Arabia is ranked 146th in the 153-country Global Gender Gap Index). So, in a society this segregated, which requires a woman’s every move to be approved by a husband or male relative, where a woman cannot mingle in public spaces and, until 2018, where women could not even drive, it’s a miracle that Haifaa Al Mansour ever managed to get this film made. And yet she did, concealing herself in a van and spitting commands via walkie-talkie as her cast and crew worked outside.

Like its director, the film’s titular protagonist is the definition of defiance. Ten-year-old Wadjda wears Converse chucks under her abaya and is slack with her Qur’an lessons—that is, until she learns her school is running a scripture-recitation contest that will award its winner a thousand riyals. There’s a green bike at the local shop that’s caught her eye, and she’s willing to do everything in her power to be able to afford it.

To reveal more of the story would be to ruin its magic, as Wadjda is, overall, an uncomplicated narrative propelled by the simplistic aspirations of a child. While some plot points do centre on Wadjda’s mother, her new husband and the folks at school, our investment remains staunchly on our plucky heroine and the machinations of her small-scale quest. But even the everyday contains within it the potent seeds of resistance: the bike acts as metonym for mobility within the kingdom, and we can’t help but read Wadjda’s success or failure as symbolical of what lies ahead for Saudi women and their freedoms.

• • •

Yellow Is Forbidden

Pietra Brettkelly, 2018 // 97 mins // DocPlay, Golden Age’s Movie Night

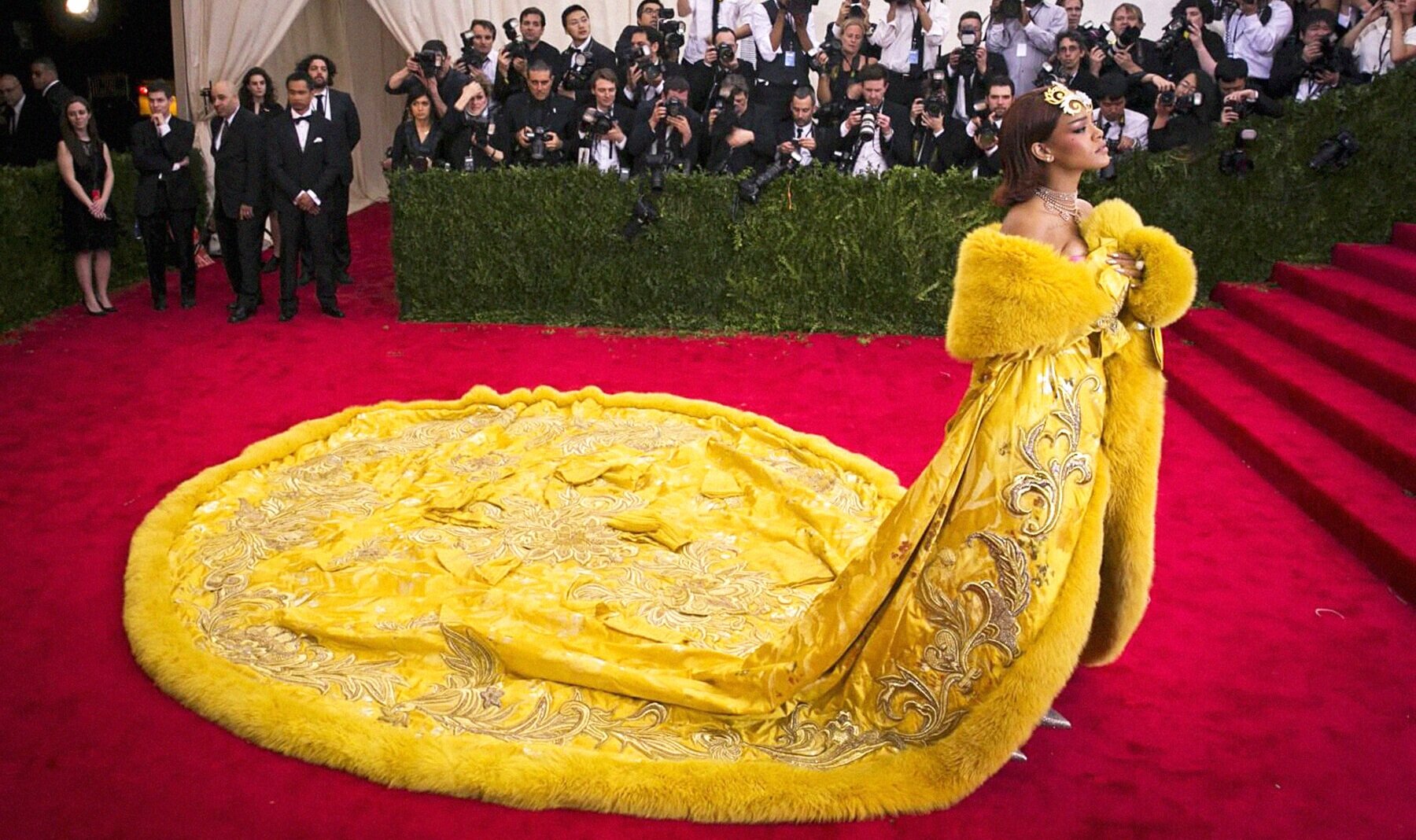

Guo Pei is the Chinese designer behind that Rihanna dress from the 2015 Met Gala. Without a doubt, the provenance of the gown (over 50,000 hours of hand-embroidery!)—along with glimpses into the glamorous world of haute couture, which is so exclusive that use of the label requires approval from France’s Ministry of Industry—is a strong drawcard of Yellow Is Forbidden. For me, though, this film’s standout aspect is its framing of Guo’s career as an embodiment of the perennial tension between ‘East’ and ‘West’, taking in its stride such themes as identity, authenticity and tokenism.

The documentary details Guo’s ascent to global fame, from her early days in the nineties up to, in 2016, her acceptance into the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture and her 2017 collection/show Legend. We learn that she juggles making traditional garments for wealthy Chinese women alongside high-fashion work for a European clientele. We gain insights into her struggles to honour her Chinese roots in an industry that shuns ‘outsider’ styles (barring periods when ‘Oriental’ or ‘fusion’ are deemed back in vogue). Most tellingly, we become privy to the pressures she faces as one of the few non-white designers in a multi-billion-dollar sector. This inevitably yokes her with the responsibility of representing her entire nation, her race—a problem she recognises, but which she feels unable to speak out against as a result of the ‘gratitude’ for being invited to the table that minorities often internalise.

The plight of some diasporic individuals who, in ‘making it’ in the West, soon find themselves displaced—or out of place—in their homelands is affectingly distilled in sequences showing Guo with her parents. While, of course, she wants them to share in her triumphs, the now-wide cultural divide means their notions of achievement differ drastically. As a diasporic success story (of sorts) myself, I found this throughline particularly resonant; what is worth a lot in one social domain can, in another, amount to very little.

Yellow Is Forbidden is not perfect by any measure; at times, its scenes of the fashion world err on self-indulgent, and, beyond giving voice to Guo, it doesn’t offer a dragon’s-eye-view understanding of assimilation, elitism, forced code-switching or global fashion’s Eurocentrism. Nevertheless, in tackling these issues through the trajectory of one person who sought and secured industry validation, the film captures—accessibly, compellingly—how success can come at a price.