Asian, Don't Raisin

by Shirley Le

I was waiting outside Bangkok Bites in Newtown. At the traffic lights opposite, a group of young white men in artfully crumpled linen shirts were huddled under an umbrella about to cross the road. Poor dudes. None of them knew the privilege of having a Viet mother who would iron out all of the creases in those shirts. I was looking for a man who had identified himself on Tinder as ‘John’: some type of East Asian (judging by how pale he was), twenty-nine years old and 182cm tall. Extra details on his bio were: Coffee. Burgers. Food. Drink. Obvs a Taurus.

John arrived kicking the rainwater off his brown leather Lacoste sneakers. It was the first time we’d seen each other IRL after chatting for a week. From those conversations I gathered that his hobbies mostly involved eating and drinking. He considered pies, spring rolls and barbecue pork buns ‘burger-adjacent foods’. His stance on coffee was more conservative. Tea was ‘for pussies’. John seemed harmless enough and I was lonely.

Whoa, you’re sooooo not 26. You look 21!

The force of his hug told me that this was a compliment. It also told me that his ratio of arm to leg day during the week was probably 2:1. Rain drops sparkled in the comb of his black hair, and there was a pearlised glow to his face that hinted at a rigorous skincare routine—it made me think of the main character in the opening sequence of American Psycho. Tilting his head upwards, he squinted at the sign hanging above the front door of the restaurant.

I thought you said we were going to a Thai restaurant?

The sharp bridge of his nose caught the sign’s neon red glow, spreading across the high plains of his cheekbones. I spied a few tiny grey hairs poking out between the fades on the side of his head. I assured him that the restaurant could be reasonably expected to serve Thai food and that Bangkok was the capital of Thailand.

Are you sure babe? I’m going to google that and if you’re wrong, you owe me a kiss!

He accentuated his threat with a light punch to my left arm. I felt the ridges of his knuckles through the chiffon of my blouse. As we stood in line, he wrapped an arm around my waist and pulled me in so that our hips were touching. My body hung against his like a tumour. I wondered if he knew what the capital city of Vietnam was and whether I had the right to be offended if he didn’t. After all, I’d never even been to Hanoi.

Babe, how old do you think I look?

John grinned like a game show host and I caught a whiff of Listerine. He fixed his gaze on me. I pretended to focus on a French bulldog who had just waddled out of the bookshop next door; it had a yellow raincoat fastened around its bánh mì body. I was hopeless at telling people’s ages. This guy possessed the self-grooming capabilities of a vampire but acted like a fifteen-year-old who spent his time watching Hollywood movies like The Hangover. How old would that make him. Really.

*

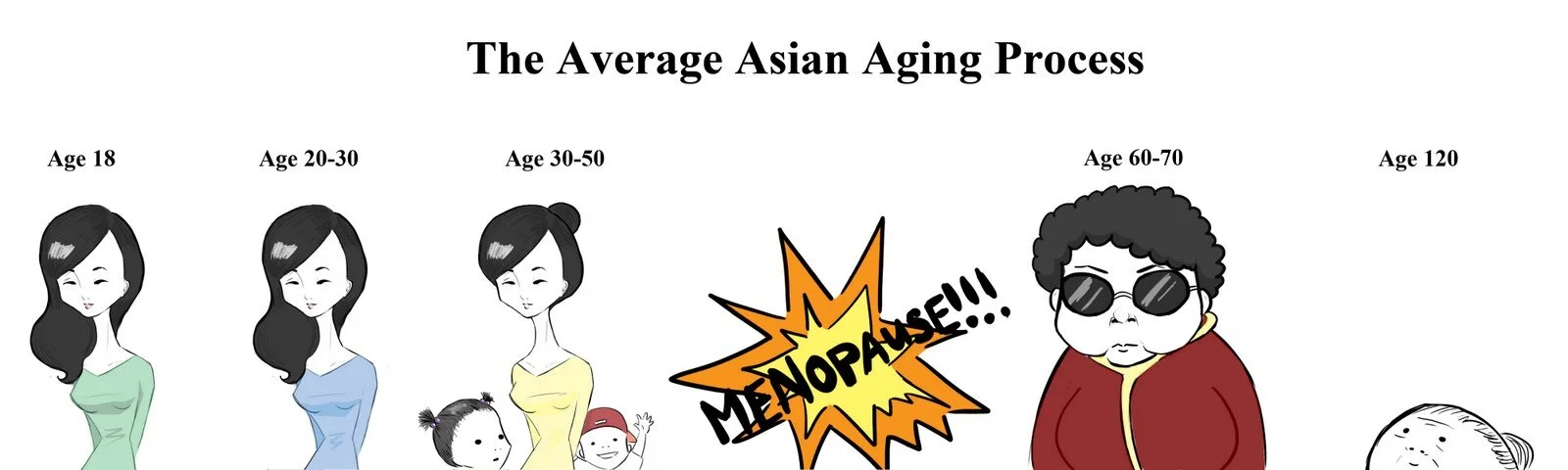

It was so humid on the train home that the pores on my face felt like they were stuffed with Glad wrap. My phone pinged. John had tagged me in a comment under a Facebook post, with a meme called ‘The Average Asian Aging Process’. Beside my name, he had put in some emojis: 😂😂😂

I scrolled back up to the meme. Drawings of Asian women at different ages were arranged side by side, charting our supposed ‘evolution’. It reminded me of another illustration that I had seen in high school during science class—‘The March of Progress’, which documented twenty-five million years of human evolution.

The Asian woman in ‘The Average Asian Aging Process’ looked exactly the same between the ages of eighteen and fifty. Slim. Pale. Cherubic. Trapped in a cocoon of perfection. Doomed to a ten-step skincare regimen brimming with niacinamide, retinol and hyaluronic acid. Every. Single. Night.

I scrolled through the other comments under ‘The Average Asian Aging Process’. Many of them, like John, had simply tagged other Asian women by their names. One comment read That’s why you should only date Asians haha while another chirped Accurate!

Before I deleted Tinder off my phone, I swiped back to ‘The Average Asian Aging Process’. I noticed that the Asian woman in the meme was illustrated with her hands tucked behind her back, like a waiter ready to take a customer’s order. My heels, stacked on the seat opposite me in the last carriage back to Yagoona, slipped on the vinyl.

*

Summer of ‘09. I was standing behind the counter of my family’s bánh xèo stall at a community fair in Chipping Norton in south-western Sydney. I was wearing an apron, my hands tucked behind my back. We were raising money to pay the school fees for several orphans living in rural Vietnam. A queue of Viets who had driven in from the rest of the area—Cabra, Fairfield, Livo and Bankstown—were waiting for their orders of turmeric and rice flour cakes, which were sizzling in frying pans, each one supervised by my mum and aunt. Each cake was flipped onto a paper plate and transferred to me. I poured on the fish sauce and arranged lettuce leaves, herbs and neon slivers of pickled carrots around the crisped edges of each bánh xèo.

Mid-pour, an aunt from the neighbouring fried chicken stall yelled out: Ê! There’s an Aussie out here. Is he from the council? The c-word sent a ripple effect through the rest of the Viets. My mum and aunt flicked off the switches on their portable stoves. I slammed lids on tupperware containing fish sauce. We were either stuffing shit into plastic bags or covering it up with picnic rugs.

We were there illegally. The oldies who had organised the event had camped out at the park since three in the morning to make sure that we could take up the entire grounds later that day, the barbecue areas in particular. Registering the event with the local authorities would mean coughing up money that no one really had and filling out paperwork that no one understood. It was a risk every year. This was why the organisers decided on the first Sunday of February as the day for the fair. Apparently no other ethnics or whites in Chippo had anything special to do that day. The park was ours.

The Aussie moved through the crowd of Viets. The pointed tip of his Akubra stood upright like a shark’s dorsal fin. Sunlight sank into the deep laugh lines dripping down the sides of his mouth. He stomped right up to the front table of our bánh xèo stall. A big DSLR hung from his neck, which bounced on his beer gut as he moved.

Heard ‘bout this from a blog, thought I’d come down to check it out.

His voice scraped through the heat. He clutched his camera and brought it up to his grey right eye. Cocked it at us.

I go to Vietnam every year, I luv it.

Snap.

Beautiful country.

Snap.

With beautiful food.

Snap. Snap.

And beautiful women.

Snap.

My mum laughed and asked him more questions about his trips to Vietnam while he circled the table taking more photos. Then she slid a paper plate with a bánh xèo on it towards me.

Con, serve him one.

I poured the fish sauce on the bánh xèo until it was drowning in the salty, pungent amber liquid. The call of the cicadas in the parklands reverberated in my ears.

Eighteen-year old me. Hands clasped behind my back. That is what I imagined his camera must have captured.

*

I was returning from the Gong Cha near Bankstown station when I heard an ancient Vietnamese proverb uttered through the wet, purple lips of a Chú who wore a button-up shirt tucked into jeans, paired with socks and sandals.

Men are very loyal and women are not.

An eighteen-year old woman will love an eighteen-year old man. And when she turns eighty-one, she will love an eighty-one year old man.

An eighteen-year old man will love an eighteen-year old woman. But when he turns eighty-one, he will still love the eighteen-year old woman.

Outside Cafe Nhớ, the men sat at a circular stainless steel table in a cloud of their own cigarette smoke. Their laughter weaved through the main street of Saigon Place, from the bronze statue commemorating Vietnamese boat people to Oscar Sports Hotel, where my great-aunt once smacked her husband after she found out about his girlfriend in Vietnam. Socks and Sandals Chú cackled so hard that he slapped his thigh and doubled over.

I walked on, sipping on the straw in my bubble tea cup like it was an inhaler.

*

The following summer, I was once again standing behind the counter of my family’s bánh xèo stall in Chippo. This time, I wore a hat (no, not a conical straw hat) from Big W, with a brim that stretched out so wide that my whole face was shielded—would be shielded—if anyone came round with a camera. As usual, I had my hands tucked behind my back, waiting for customers.

That year, we got a family friend, Chị Thủy, to help out with the bánh xèo. She was a freshie, married to one of my cousins. I didn’t know her very well but I had heard plenty of gossip about the marriage from eavesdropping on my mum’s telephone conversations. As Mum paced around the backyard with her hair bound in rollers, she discussed the discrepancy between the ages of the groom and the bride. He, forty-three. She, twenty-two. Mum jabbered on: about how beautiful Chị Thủy was and how her willowy gait had ’rescued’ her from a life in the rice paddies.

Before she got down into a squat with my aunt and mum at the frying pans, Chị Thủy looped a scrunchie through the long, silky hair that trailed down her back. The forest green v-neck shirt she had on accentuated the milky pallor of her skin.

Midway through the fair, a bunch of Viet oldies, all men, made their way through the crowd. They each had a DSLR slung around their neck.

The leader of the group corralled us like a town crier.

Mày Cô, mày em, mấy Chị… we’re part of the local photography club. Can we take some photos? We’ll share them with you on the community fair’s website tonight.

He distinguished himself from the other members, with a black beret and a moustache that rivalled Mr Pringles’.

My aunt chuckled and motioned the photographers towards Chị Thủy and me.

Sure, but get the young ones. I don’t want to see my wrinkles blown up on a computer screen!

I heard the cameras clicking as I handed over plates of sunny bánh xèo to people in the queue. A few photographers lingered near Chị Thủy.

Ah, looks like we have some bánh xèo beauties here today!

I watched as the lens of one camera coiled in and out like an octopus’ tentacle. It reminded me of a scene from a black-and-white movie called It Came From Beneath the Sea that I had watched on YouTube. A giant tentacle, suction pads pulsating, snaking through the streets of a city, wrapping itself around a town hall clock before smashing it to the ground.

When the photography club finished taking photos, their president raised a hand in thanks and the men moved on to another stall opposite the fair selling squid jerky salad.

The next day, all the participating stallholders received an email from the organisers thanking us for contributing to a good cause. They had raised over $40,000 to pay for the orphans’ school fees that year. At the bottom of the email was a link to the photography club’s online forum. The club had uploaded the photos there.

I stood behind my dad as he looked through them on our family computer. The first thirty or so photos showed women at the other food stalls. One was of a Cô ladling congee and mauve cubes of pig’s blood into plastic bowls. Another shot captured a Chị from the stall neighbouring ours. She was dunking fish sauce marinated chicken wings into a deep fryer, all while smiling at the camera.

Then there were the photos taken at our fam’s bánh xèo joint. I cringed when I saw my sweaty red face under that Big W hat I had chosen to wear. The last photo showed Chị Thủy and me. We were standing behind the front table that had dozens of bánh xèo stacked on it. Both of us were smiling and waving, our hands clad in plastic gloves stained yellow with turmeric.

Ba clicked out of the image reel and continued scrolling through the photography club’s forum page, hoping to see more of their work.

As the grey scroll bar slid further down the web page, five more photos were revealed, each of them looming large on the screen. Long strands of hair falling over angular cheekbones. A milky cleavage against dark green fabric. Whoever had taken the photos had angled their lens in a way that stared down Chị Thủy’s shirt. One shot even showed the pinky-sized plastic clasp that held together the front cups of her bra.

*

I was sitting in the waiting room of a gynaecologist, thumbing through Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer. The air con was cranked up so high that I tried to generate some warmth by jiggling my knees.

On the fourth page, I read: ’She had a mind like an abacus, the spine of a drill instructor, and the body of a virgin even after five children. All of this was wrapped in one of those exteriors that inspired our Beaux Arts-trained painters to use the most pastel of watercolors and the fuzziest of brushstrokes. She was, in short, the ideal Vietnamese woman.’

The receptionist cleared her throat. She beckoned me over with a fluoro green nail that had been filed into a perfect oval. I put down my book and walked over to the counter. She handed me a biro for the Patient Details Form that I had to fill out before the gyno could poke into my uterus, remove a polyp and get it tested for cancer. I was there by myself. I had not told anyone in my family, because then I would have had to explain that the doctors found the polyp during a pap smear. My family had taught me that ‘only’ married women had pap smears. They also taught me that men only married virgins.

I underlined the lines that I had just read in The Sympathizer. The blue ink skid across the page like a serum. It dashed right through the words rather than under them. What if I did have cancer? How would I explain it to my family? I had the mental agility of a cotton ball and the spine of a slug.

*

Chị Thủy’s cleavage was still up on the family computer’s screen as my dad rang the charity fair organiser.

I’m not sure if you’ve reviewed all of the photos that were taken but we have come across some… unflattering… images taken of one of our family members.

I stood behind my father on his right hand side where the phone was pressed to his ear. Being taller than him, I leaned down, the tip of my nose grazing the edge of his tanned ear. I burst out: Well actually, the photos are disgusting!

My father’s knuckles bulged white but his voice stayed calm: If it’s not too much trouble to remove them—

I tilted my head so that I could yell more easily into the mouthpiece: DELETE THEM AND MAKE THAT PERVERT APOLOGISE TO HER!

My dad stumbled away, his black rubber slides squeaking as he gripped the edge of our computer desk. He managed a soft Cám ơn before he hung up.

Turning to me, the freckles across his cheeks flushed purple, Dad whispered, Don’t ever embarrass me like that again.

I ran to my room and slammed the door behind me.

*

A spiky cartoon explosion bubble bearing the words ‘MENOPAUSE’. I held my phone in my left hand while my right thumb and index finger zoomed in to the meme that showed what happened to Asian women after this particular stage in life. The triple threat of exclamation marks after ‘MENOPAUSE’ projected a sense of foreboding.

It was just me and a teenage Viet boy left in the carriage. He sat a few seats away and was speaking on his phone. There was a slight lisp in his voice.

Hey Mẹ can you pick me up from Banksthown Stathion?

He hung up and slurped at the dregs of leftover ice in his raspberry slushie.

I wondered if his mum looked like the Asian woman in the meme—sixty years old, stout, with a frizzy halo of hair and sagging cheeks. Did she give her son that upturned nose, those monolid eyes and eyebrows that high-kicked their way across his swollen forehead? She must have been parked outside the station, watching the barriers, waiting for her beloved baby gremlin to appear.

You got a stharing problem?

The kid pointed the straw of his slushie cup towards me as he yelled across the carriage. I kept my eyes on my phone.

*

The polyp isn’t malignant. That means you can have children!

My gynaecologist, a white man who always wore a different pair of Gucci loafers at each of our appointments, grinned and chucked his hands in the air.

Yay, I don’t have cancer.

My voice came out all squeaky. I had been holding my breath until that point. The gynaecologist leaned back in his chair.

I guess I’ll see you next time when you’re having a baby, eh?

As he winked at me, I saw that he had ten Thank You cards neatly arranged in a row on the floating shelf behind him. He doubled up as an obstetrician.

Since that appointment, I had tried to write about how the gynaecologist had cut the polyp out of my cervix and held it up to the cold light—a trembling red membrane, approximately a thumbnail wide, clinging to the edges of his tweezer.

Seven new open documents, all of them empty. What was the point of being a writer if I couldn’t split myself open and scoop out all the quivering bits inside of me?

*

Under the mood lighting inside Bangkok Bites, the edges of John’s vampiric face appeared grainy. He could have easily been in a Wong Kar-Wai movie. Before dipping a stuffed chicken wing into sauce, he waved his chopsticks in my direction.

Tell me what you write about.

I waved my chopsticks back at him, tracing them in the imaginary path of a lazy fly.

Race, gender, culture, identity…

That chicken wing must have been extra stuffed because he spluttered into a napkin before I could elaborate any further.

He leaned forward, lips slick with grease.

Why do you choose such obscure things to write about? I’d write about turning thirty. That is sooooo much more relatable!

I clutched a chopstick in my right fist, leaned forward and stabbed the pointed end into the flesh of a chicken wing.

Yeah, maybe you’re right.

Shirley Le is a Vietnamese-Australian writer from Western Sydney. She is a Creative Producer at Sweatshop: Western Sydney Literacy Movement and holds a Bachelor of Arts degree from Macquarie University. Her short stories and essays have been published in Overland, The Guardian, SBS Voices, The Griffith Review, Meanjin and several Sweatshop anthologies. Shirley is currently working on her debut novel as the recipient of a 2019 Affirm Press Mentorship.